Body, Mind, and Soul | Renaissance Humanism

People are moved to wonder by mountain peaks, by vast waves of the sea, by broad waterfalls on rivers, by the all-embracing extent of the oceans, by the revolutions of the stars. But in themselves they are uninterested.

— Francesco Petrarch, quoting St. Augustine's Confessions in Ascent of Mont Ventoux, 1336 —

"The sinking sun and the lengthening shadows of the mountain were already warning us that the time was near at hand when we must go. As if suddenly wakened from sleep, I turned about and gazed toward the west. I was unable to discern the summits of the Pyrenees, which form the barrier between France and Spain; not because of any intervening obstacle that I know of but owing simply to the insufficiency of our mortal vision. But I could see with the utmost clearness, off to the right, the mountains of the region about Lyons, and to the left the bay of Marseilles and the waters that lash the shores of Aigues Mortes, altho' all these places were so distant that it would require a journey of several days to reach them. Under our very eyes flowed the Rhone. While I was thus dividing my thoughts, now turning my attention to some terrestrial object that lay before me, now raising my soul, as I had done my body, to higher planes, it occurred to me to look into my copy of St. Augustine's Confessions, a gift that I owe to your love, and that I always have about me, in memory of both the author and the giver. I opened the compact little volume, small indeed in size, but of infinite charm, with the intention of reading whatever came to hand, for I could happen upon nothing that would be otherwise than edifying and devout. Now it chanced that the tenth book presented itself. My brother, waiting to hear something of St. Augustine's from my lips, stood attentively by. I call him, and God too, to witness that where I first fixed my eyes it was written: 'People are moved to wonder by mountain peaks, by vast waves of the sea, by broad waterfalls on rivers, by the all-embracing extent of the oceans, by the revolutions of the stars. But in themselves they are uninterested.'"

This account by Francesco Petrarch of his journey to the summit of Mont Ventoux in a letter to a friend is a symbol of the new attitude sweeping across Europe during the 14th century. For much of the previous thousand years, medieval society had clung to the message of Augustine's The City of God, of the promise of heaven as the hope of mankind. It had thus failed to address serious religious, political, and social problems that led many to call this period of Western history the "dark ages." Petrarch, a well-educated Italian poet, was speaking of a new philosophy that put mankind at its center and sought to make this world a better place rather than awaiting the joys of eternity. His followers became known as "humanists," and their embrace of their own experiences and desire to improve their lives was one of several driving forces behind this new epoch of history: the Renaissance.

Scholasticism

Before the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the mid-5th century, learning began with ignorance. Scholars asked the question "why" when they approached a new subject, whether it was mathematics, science, or morality. This was known as the "Socratic Method" because it originated with the Greek philosopher Socrates, and it was the foundation of Greco-Roman education for centuries. However, with the rise of the Latin Church to the center of the European collective consciousness, medieval scholars chose to move away from Socratic dialogues and instead approached education from an expressly-Christian point of view. They began with the assumption that Scripture and Church dogma was true and then investigated new questions from that standpoint. This "school" of educational philosophy was known as "scholasticism."

The greatest work of medieval scholasticism is unquestionably St. Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica, or "Summary of Theology." The author sought to create a systematic picture of Christian teaching and then defend it from the many attacks by heretics that were common in those days. The Summa Theologica remains a standard reference work for both Catholic and mainline Protestant denominations and is generally viewed as one of the best pieces of moral philosophy ever written. Aquinas and other scholastics like Anselm of Canterbury, William of Ockham, and Peter Abelard worked to reestablish education and literacy during the Middle Ages. They founded universities in major cities across Europe, copied and translated hundreds of Greek and Roman works once they had been recovered in the West, and did whatever they could to keep the flames of learning and culture alight during one of the darkest periods in world history.

However, as Europe began to emerge from the so-called "dark ages," many intellectuals began to question scholasticism as the best method for education. The corruption of a minority of powerful men in the Church, as well as the widening gulf between doctrines and canons and the Scriptures, caused some Christians to long for a return to the simple teachings of the Bible. Though not the only cause of the Renaissance, this revisionist approach to philosophy was one of the driving forces that brought about the revival of European thought and culture in the 15th century.

Humanism

The term "humanism" must be defined in its proper historical context because the word today means something very different than it did six centuries ago. Whereas humanism today is generally seen as a rejection of any divine influences in the world, Renaissance humanism sought to elevate mankind through education in the "humanities"—grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy—as well as to renew Christianity by returning it to its Scriptural roots. The vast majority of Renaissance humanists were Christians, but they often wrote books and treatises that criticized medieval Church practices or questioned its teachings. In fact, several popes called themselves humanists, particularly Pius II, Sixtus IV, and Leo X. Efforts by modern humanists, therefore, to claim that the Renaissance was a rejection of the medieval Christian worldview are wholly inaccurate. Later humanists, especially during the Enlightenment, sought to remove Christianity from Western thought, but in the early stages of Europe's revival, the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth and his followers were at the forefront of the Renaissance.

The humanist movement developed unique national characteristics and differences as it spread across Europe, helped along by Johannes Gutenberg's invention of movable type in the 1440s. However, all humanists shared three common beliefs regardless of where they lived: a love of learning, a desire to return ad fontes, "to the sources," and the goal of improving the "body, mind, and soul" of their audiences. Each of these stemmed from the writings of Francesco Petrarch, the "Father of Humanism."

In his book The Library: An Illustrated History, Stuart Murray credits Petrarch with renewing interest in libraries and collections of the written word. With few exceptions, libraries had almost disappeared from Europe during the Middle Ages. (Indeed, the English monk Bede of Northumbria was widely viewed as one of the wealthiest individuals in Europe because he owned about two hundred volumes in his personal library in the late 7th century.) By the 15th century, scholars like Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio were searching northern Italy for Greek and Latin manuscripts to copy and translate for their libraries, and monarchs like Henri II of France and Henry VII of England were employing monks and secular intellectuals to compile books and establish national libraries as resources for scholars. Some Italian princes even went to war over the possession of printed material; for example, Poggio Bracciolini urged the powerful Medici family to invade rival city-states to seize their collections. Books became treasures worth far more than their weight in gold because they held the keys to knowledge and self-possession, and the "Renaissance men" were willing to do almost anything—even kill—to possess them.

Why was this the case? Quite simply, Renaissance scholars hoped to secure the fontes, or "sources," of knowledge that had been lost during the Middle Ages. They sought wisdom of earlier times and hoped to strip away the scholastic dogmas of the medieval Church. Scientists read copies of Aristotle instead of the pages of Scripture to determine the Earth's position in the cosmos. Mathematicians perused the works of Pythagoras and Archimedes taken from Islamic libraries during the Crusades to develop weapons and gain an understanding of humanity's most fundamental language. Theologians like John Wycliffe and Jan Hus returned ad fontes by reading the New Testament in an effort to revive Christian teachings and bring them in line with the words of their Savior. For "Renaissance men," the source material was instrumental in the gaining of what Desiderus Erasmus called "true wisdom" and brought them closer to it source—the Almighty.

Of course, the mind was not the sole focus of Renaissance humanism; its adherents also hoped to enrich the body and the soul. New discoveries in medicine and anatomy emerged from the brutal crusades in the Near East. Leonardo da Vinci, famous more for his artistic contributions to the Renaissance, did much to advance human knowledge of the brain, the eye, and the spine. His Vitruvian Man and other sketches of anatomy made from dissected cadavers taught generations of physicians how the body worked. The French surgeon Ambroise Paré used Roman techniques to treat battlefield wounds through a combination of turpentine, egg yolk and rose oil instead of the then-common application of boiling oil. He also trained midwives at a school in Paris, which led to a decrease in maternal mortality rates, and he designed and built artificial limbs for maimed soldiers. Other medical scholars like the Englishman William Harvey and the Flemish Andreas Vesalius studied the body and determined how the nervous and circulatory systems worked. The "Renaissance men" enriched the body by discovering new methods to treat illnesses and wounds, and they paved the way for later innovations that are the basis of modern medicine today.

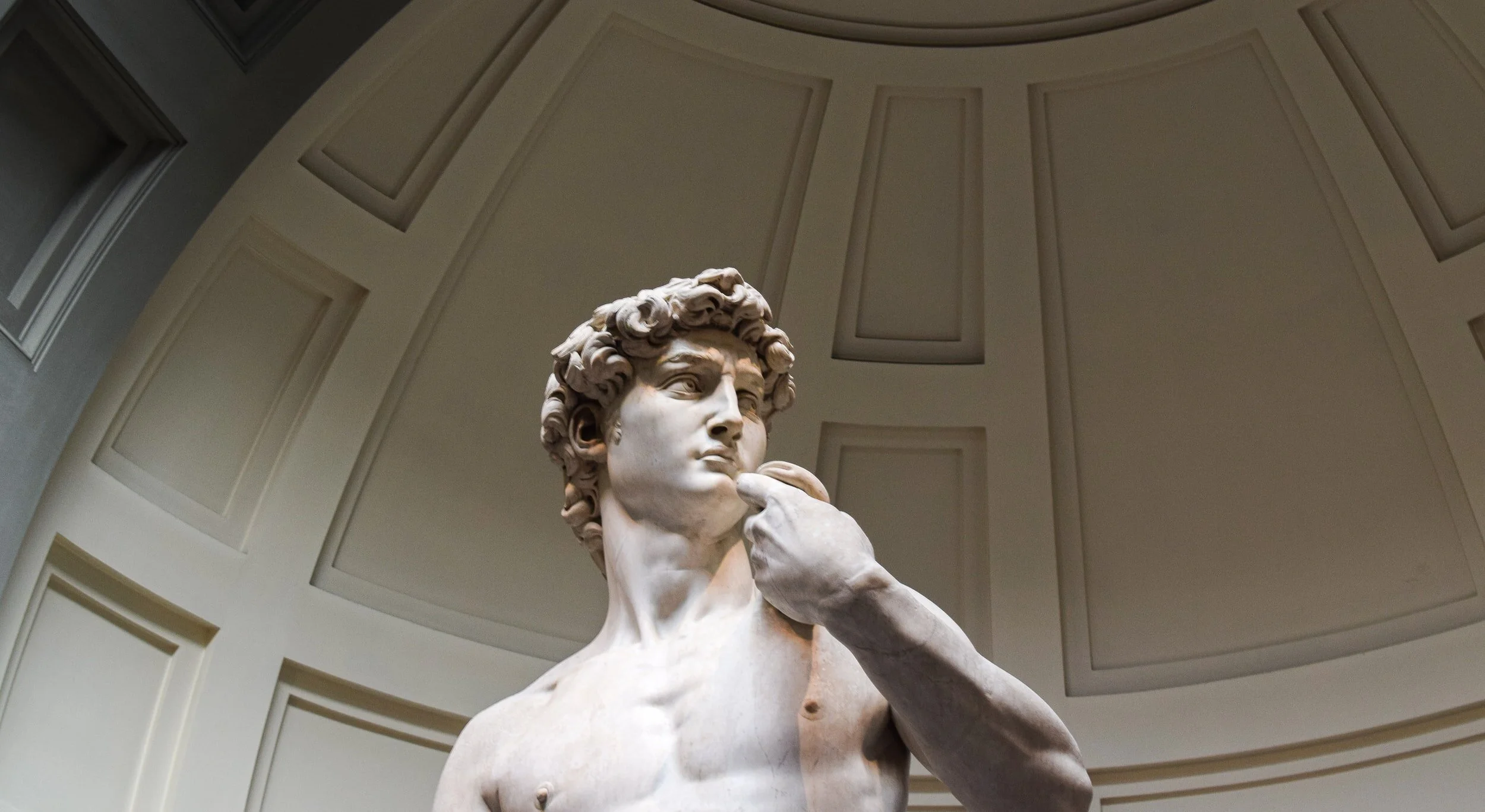

The enrichment of the soul by Renaissance humanists took several forms. In terms of religion, the return to sources brought about the Reformation—which did lead to a revival of Scripture in both the Catholic and new Protestant churches but also, tragically, sent hundreds of thousands of souls into the next world during religious wars. More generally, humanist artists hoped to lift their audience's spirit by their works. Painting, sculpture, architecture, and other forms of visual and written art began to shift away from religious themes and instead portrayed daily life and beautiful landscapes. The works of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo di Lodovico, and Sandro Botticelli are triumphs of humanist art because they depict reality and show the beauty of the human form. Albrecht Dürer, who we have already discussed earlier this season, revived classic Greco-Roman myths in his paintings and woodcarvings. William Shakespeare, though he lived at the tail end of the Renaissance, incorporated a renewed understanding of humanity at the center of stories and sought to portray the great men and women of history as agents of change with their own goals rather than instruments of divine will, as was common in medieval literature. Each one of these "Renaissance men" were self-made, using the skills they had developed through training at the hands of other masters of various crafts to create masterpieces which lifted audiences out of their daily lives and allowed them to see greatness in the world, and in themselves.

Learning from History

Our world today is the product of Renaissance humanism. While we may have strayed from the religious centricity of those times, most of us still believe that we have a duty to make our community, our family, and our own lives better by our actions. Regardless of our spiritual beliefs, we no longer submit to fate and accept reversals as divinely-ordained; instead, we strive to overcome them and to make our destiny our own. Renaissance humanists teach us other lessons from the past, each one stemming from the themes which united the many national and cultural movements of six centuries ago.

A love of learning is a part of being human. I don't mean sitting in a classroom listening to teachers like me drone on each day. I mean reading a new book, hearing an interesting podcast on a new subject, or learning a new skill. Each one of us knows what it feels like to learn something truly new—it is exciting, and it makes us want to learn more. It is sometimes difficult in our busy lives to take time out to learn, but we can become Renaissance men and women thanks to the wonders of modern technology. Speaking personally, in recent months I've been learning more about cooking and trying new recipes. It was something I'd never thought about in years past, but I've become fascinated with how people prepare similar ingredients and get wildly different results. Before the pandemic upended my classroom and everything else in the world, I occasionally made food from different cultures for my World History students. They really enjoyed my French foie gras, at least until I told them what was in it! There are amazing cooking podcasts and websites out there, and I think I've added to my "Renaissance man" repertoire by becoming a self-made (though not a great) cook. Find something that you've always been interested in learning more about, and then take some time each week to try your hand at it. Become a self-made man or woman in the style of the Renaissance humanists. Trust me, you'll enjoy it!

The Internet has given us the sum of human knowledge at our fingertips, but it has also become a tool for ignorant and malicious actors to spread disinformation at rates never before thought possible. It is tempting to believe whatever you read on a website because it looks credible, but here the Renaissance humanists have a warning for us. Return ad fontes, "to the source." Don't simply accept something you read—whether about politics, religion, health and fitness, or the color of a dress you see on social media. Go to the source. If you hear that a famous person has said something problematic, read up on it for yourself. Look at the context. Perhaps they did say it, but maybe there are biases and distortions in the reporting. It happens in every facet of life; people get lazy or write sloppily, or maybe they are trying to get you to believe or behave a certain way. Check your own biases when you are learning and reading, and go to the source whenever you can. (Also, find podcasts that go to the source—I know of a good one with two guys talking about history in short, easy-to-hear lessons!)

Lastly, and most importantly, take some time each day to enrich your body, your mind, and your soul. I'm not going to tell you to go to the gym, eat healthy, or go to church; that's not my place here in this podcast. Instead, I'll just say that spending your day working at the computer or having Zoom meetings with colleagues is necessary, but it's not always fulfilling. Take a break. Read a good book or listen to a great audiobook or podcast. Learn a new skill. Enrich yourself. We are all more than just our work or our instincts—we can become self-made individuals with unique character traits that make us more than who we were born to be. Use the example of the "Renaissance men" in this podcast. Find greatness in the world and in yourself.