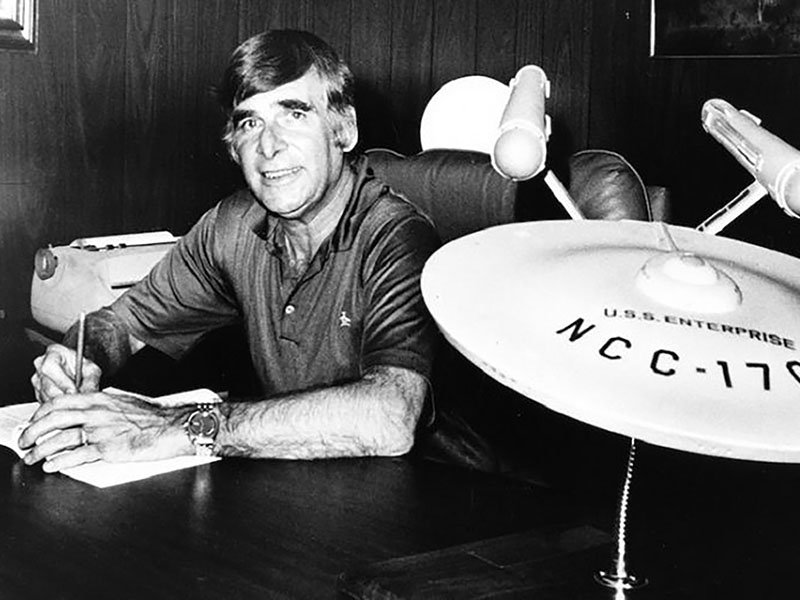

Gene Roddenberry | The “Great Bird of the Galaxy”

“I'm always tempted to ask you why we can't talk about Star Trek more.”

- Joe Parker, “What to Watch” discussion, Season 2 of 15-Minute History -

Hear me out—Joe talked about doing an episode about Star Trek way back in 2019, and whether or not you like the show, its creator was a fascinating man with some very interesting stories to tell and lessons to impart. Plus it’s the end of a long season, and Joe is going to be closing us out in two weeks with one of his favorite writers, so I thought I’d do the same. And trust me—this won’t be some geeky lesson about phasers versus disruptors or the mechanics of warp drive.

Eugene Wesley Roddenberry was a legend of Hollywood in his day. He grew up reading science fiction serials and adventure novels like C.S. Forester’s “Horatio Hornblower,” and they inspired him to become a writer. After a career in the US Army Air Force, as a commercial pilot, and a Los Angeles police officer, he started writing television scripts and shopping them around Hollywood. His antics in the office and in his personal life earned him respect and disdain in equal measure, and his stories reflected both the events of his life and the beliefs he held. The tales he told showed audiences a vision of humanity that was beyond greed, beyond war, beyond poverty, and largely beyond our reach even today.

The Show

The 1960s was a time of change in Hollywood. Most of the first-generation studio executives like Jack Warner and Walt Disney had either retired or died, and large corporations were buying motion picture companies left and right. They then appointed chairmen who knew nothing about how to bring stories to life and instead made films and television shows meant to sell products rather than entertain audiences and provoke them to deep thought. One of the exceptions was a small studio called Desilu, founded by the husband-and-wife team of Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball (both beloved by audiences for I Love Lucy). After their divorce, Desi had left Lucille in charge of the studio, which had not been successful in recent years. So when Gene Roddenberry approached Desilu with a script called “The Cage,” Lucille Ball agreed to finance its production—earning her a central place in the history of Star Trek.

“The Cage” featured Jeffrey Hunter in the role of Captain Christopher Pike of the USS Enterprise and Majel Barret (whom Roddenberry had met on the set of The Lieutenant and with whom he was now having a very public affair) as the quiet but competent Number One, a progressive television icon as a woman who was second in command of a starship. Pike and his crew faced off against aliens who were trying to enslave humans to rebuild their civilization destroyed by a nuclear war, and the story ended with a speech by Pike about the value of human freedom.

Once the pilot had been shot, the studio took it to NBC, which passed on it for their network but still liked the idea of a western-themed science fiction show. Roddenberry was crushed, but in a second meeting, NBC’s executives offered him and Star Trek another chance. The result was “Where No Man Had Gone Before,” a second pilot that replaced Hunter’s Pike with William Shatner as James T. Kirk and Barrett’s Number One with Leonard Nimoy’s coldly-logical Mr. Spock. This story involved a character being given god-like powers and becoming a tyrant, and it ended with a bare-chested battle between Kirk and the man-god, which appealed to the action-oriented NBC executives. They ordered a full season with Roddenberry at the helm, and Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966.

In many ways, Gene Roddenberry’s career was the story of him working hard, achieving his dreams with a fair amount of luck, and then sabotaging himself. After only ten episodes, Star Trek was out of scripts to produce because Roddenberry kept rewriting them. This caused delays and resentment from the hired writers, but the show managed to produce a complete run of 29 episodes. The most contentious moment in the offices was over the best episode of Star Trek, “The City on the Edge of Forever.” Its writer, Harlan Ellison, created a dystopian vision that was certainly interesting but impossible to produce on budget, so Roddenberry rewrote it without permission and changed several key story elements. Ellison was furious; he tried and failed to pursue legal action, and other high-profile science fiction writers like Isaac Asimov distanced themselves from Roddenberry as a result.

The cast of Star Trek was also routinely at each others’ throats. William Shatner had been hired as the show’s “leading man,” but when he learned that Leonard Nimoy was receiving more press attention as Mr. Spock, he worked behind the scenes to undermine his co-star. Roddenberry jumped into these conflicts and penned public letters shaming both actors, who were becoming so petty as to criticize each other’s hairstyles. In hindsight, it is a miracle that Star Trek was renewed for a second season, but NBC saw potential in the Kirk-Spock dynamic. They elevated DeForest Kelley’s Dr. Leonard McCoy to “also starring” status to play his emotional character of the logical Spock, with Kirk providing the balance between passion and reason in a Socratic dialogue on television.

The second season of Star Trek was more popular with audiences because its shows focused on characters more than monsters. This change occurred because NBC insisted that Roddenberry be moved out of the writing process and replaced by Gene L. Coon, a well-respected Hollywood veteran. Roddenberry still reviewed scripts and penned notes, which Coon largely ignored, so he and Majel Barret spent most of their time building a connection with the audience and science fiction authors or else attending fan conventions (a new phenomenon at the time) to drum up support to keep Star Trek on the air. Cast and crew problems continued to plague the show, and Roddenberry encouraged it behind the scenes while publicly criticizing the actors. As the season wound down, NBC tired of the space fantasy and planned to cancel it. Only a fan-organized campaign that sent hundreds of thousands of letters to the NBC production offices demanding its renewal saved the show.

But the third season would be Star Trek’s last. It had a few memorable episodes, among them “Plato’s Stepchildren,” which broadcast the first interracial kiss ever seen on television between Captain Kirk and Lieutenant Uhura. Two of the worst episodes of Star Trek also limped their way onto the screen that year: “Spock’s Brain,” where the character’s brain is stolen by sexy space hippies, and the series finale “Turnabout Intruder,” which features a body-swap between Captain Kirk and a former lover who wants to command a starship. Although Roddenberry’s name still appeared on the title credits as the show’s creator, he had largely moved beyond Star Trek.

The Man

Gene Roddenberry was a man of staggering contradictions. He was an unquestioned progressive in his politics and believed in race and gender equality at a time when America was not ready for such radical ideas. His humanistic qualities were seen in his rejection of any form of religion and constant inclusion of god-like characters who turned out to be charlatans or villains. And his desire for peace at a time when nuclear superpowers glowered at each other and threatened the Earth with atomic extinction reflected his “give peace a chance” pacifism.

And yet, Roddenberry was also a typical man of Hollywood decades before the “Me Too” movement. His affair with Majel Barrett destroyed his marriage and hampered his career—he often took time off in the middle of the day to be with her, causing delays on set. His misogynistic attitudes led to the ridiculously-short skirts and revealing costumes seen on every episode of Star Trek as well as some fitting sessions with actresses that recall the “casting couch” of Harvey Weinstein. Roddenberry was also accused of sexual harassment by Nichelle Nichols and other female cast and crew members. And his comments about African Americans so enraged Nichols that she considered leaving the show. Only a conversation with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., convinced her to stay when he pointed out that she was the only African American actress on television in those days who was not in a domestic servant’s role.

The Wilderness

Joe Parker once told me that “the 1970s were like the hangover after a really great party.” This was true in the United States, and in Gene Roddenberry’s life. When Star Trek went off the air in 1969, his career stagnated because he was typecast as a science fiction writer. He still wrote pilots for sci-fi and other shows, and some went into production. he also wrote movie scripts, none of which are worthy of mention here because they were so bad. But Star Trek lived on in syndication, being sold to individual TV networks and watched by millions of fans every day (including my mother and her brothers, who are responsible for my fandom and thus this episode). Perhaps the greatest tribute paid to Star Trek in those “wilderness years” came in 1977 when NASA named its first space shuttle the Enterprise and invited Roddenberry and the show’s cast to attend its roll-out alongside President Gerald Ford.

There was also a growing demand for more Star Trek among sci-fi fandom. Magazines printed in basements told more stories of the Enterprise crew’s five-year mission, and fans dressed as characters and aliens at conventions around the world. There was a brief Star Trek animated series in 1973-74, but Roddenberry had little to do with its production beyond reviewing scripts—his toxic relationship with NBC and the actors made a larger role impossible. As the show’s popularity surged again, Paramount Pictures purchased Star Trek and approached Roddenberry about a new series.

That changed in 1977 with the commercial and critical success of George Lucas’ Star Wars. Paramount turned the new Star Trek show into a movie, which should have been Roddenberry’s shining moment to return to Hollywood’s A-list. But he clashed constantly with the writers and drove the film’s budget so high that Paramount considered shutting the production down. Star Trek: The Motion Picture saw the return of the Enterprise and its crew for new adventures in the final frontier, but Roddenberry was out. When sequel talks began, Paramount “promoted” him to the role of “executive consultant,” paid him a handsome fee to keep his mouth shut, and then made five more movies without listening to a word he said. Roddenberry was so outraged at plot elements in both Star Trek V and Star Trek VI that his lawyer, Leonard Maizlish, leaked plot details to the press and told reporters that Roddenberry said neither film was “real Star Trek.” Though he still had an office on the Paramount lot and was beloved by millions of fans, the self-proclaimed “Great Bird of the Galaxy” was little more than a figurehead with no real power over a vast production machine that kept Star Trek on-screen long after its creator had died.

The Next Generation

The success of the Star Trek films convinced Paramount that it was time to bring the franchise back to television. Early conversations among producers and executives always started with whether or not they wanted to work with Roddenberry. But as the series’ creator, the job of executive producer was his for the taking. He refused at first, wanting nothing more to do with Paramount and the people who had so corrupted his vision of a conflict-free future. But when told that the show would proceed without him, Roddenberry flared up. “I’ll show them that no one else can make real Star Trek!” he roared to his producer and friend Bob Justman.

The casting of Star Trek: The Next Generation focused on who would replace Captain Kirk in the center seat of the USS Enterprise. When Justman attended a reading of Shakespeare by the classically-trained British actor Patrick Stewart in Los Angeles, he knew he had found the new captain. The studio opposed having a bald man in the leading role, but resistance was futile; Roddenberry insisted that “in the future, no one will care” if a man were bald. Once the cast was complete, Star Trek: The Next Generation premiered in 1987 with “Encounter at Farpoint” and featured Q, played by John de Lancie, as the best of Roddenberry’s many god-like antagonists. The premiere was a success and set the stage for a seven-year run and three spin-off shows.

The story of the original series’ production has filled many books, but the first two years of The Next Generation could almost meet that. Roddenberry quickly returned to his old habits of stealing credits, rewriting scripts, and harassing employees. He once called an assistant into his office and shared bizarre and grotesque sexual fantasies with the young man with absolutely no prompting whatsoever. Most of the chaos that was not caused by Roddenberry’s meddling with scripts or drunken rants about women or other people “not getting the difference between shields and deflectors” was caused by the unethical or illegal behavior of his lawyer, Leonard Maizlish. Having spent more than three decades at Roddenberry's side, Maizlish believed himself to be his client's "voice." His efforts to undermine the original series' movies already made him a villain in Paramount's mind, but his shenanigans on The Next Generation’s production are the stuff of legend. After decades of alcohol, stimulant, and cocaine use, Roddenberry's health had begun to fail him, so he delegated more and more of his work to Maizlish. He wrote letters to fans and critics and attended meetings when Roddenberry was too drunk, high, or sick to be there. But as season one wrapped up, Maizlish began breaking into writers' offices, stealing scripts, and rewriting them in a clear violation of writing guild rules. He also lied to studio executives about who had written episodes and berated or threatened anyone who challenged him with legal action. David Gerrold, a writer and producer on TNG, later recalled thinking during a meeting where Maizlish was standing next to an open office window, "David, go do it, go push that bastard out of the window. They'll give you a medal!" How much of Maizlish's actions were sanctioned by Roddenberry is unknown to this day, but the fact that the show's creator was in failing health and represented by one of Hollywood's most unethical creatures nearly ended the franchise.

The second season got better thanks to the promotion of Maurice Hurley to showrunner status. Hurley, a veteran of many successful shows, simply ignored Roddenberry's "wacky-doodle" rants and did his best to ban Leonard Maizlish from the set and production offices. With him came producer Rick Berman, who took over the financial side of the production from Bob Justman, a Roddenberry acolyte unable to say "no" to his friend. The third season finally found its footing with the arrival of Michael Piller, whom I believe was "the man who saved Star Trek." Roddenberry had always insisted that the Enterprise crew could not have any conflicts with each other, but conflict is the essence of good drama. Hurley had ignored this, and Piller followed along while also shifting the show from "monster of the week" episodes to personal stories that made the audience fall in love with the characters. He remained on the show for the rest of its seven-year run and, with some highs and lows, ensured that Star Trek would continue.

The End

Roddenberry's drug and alcohol use led to serious health problems at the end of his life. He suffered from cardiovascular disease and encephalopathy, and his regular use of stimulants to keep working long into the night years earlier led to multiple organ failures. By 1989 he was confined to a wheelchair, and a series of strokes left him partially paralyzed. His last public appearance was at a Star Trek convention in late 1990, and he attended his last meeting on the Paramount lot—a screening of Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country—in September 1991. Three weeks later, on October 24th, he died of cardiac arrest while at his doctor's office. His funeral was attended by cast and crew members, as well as Hollywood friends and members of his family. Nichelle Nichols, seeming to have forgiven him for their past problems, sang two songs she had written, one simply titled "Gene." He was cremated, and some of his ashes were sent into the final frontier in 1992.

Legacy

What can we make of Gene Roddenberry as students of history? As a man, he was stubborn, angry, and often got in his own way, so we can learn from his mistakes and try not to do the same—helped along by not employing scoundrel-lawyers and making obscene phone calls to underlings at the office. Jonathan Frakes, the actor and director at the center of some of Star Trek's finest moments, put it best when he said that "Gene Roddenberry was a dreamer." And in this, I think, we have his real legacy. Roddenberry's series showed humanity in a better light than we stand in today, a world without war or poverty. The path Earth took to get there in Star Trek involved a world war that cost six hundred million lives. Perhaps ours will not have to go that far. Permit me to sound optimistic, but even amidst the turmoil our planet has seen across the pages of history, and especially these past two years when it seems like we're getting entire chapters of history books every couple of weeks, I truly believe that each one of us can rise above these challenges as individuals. Maybe we won't live in a world united under one government or without war—I tend to think the first is undesirable and the second impossible—but that, I think, is not the true message of Star Trek. Star Trek is about individuality, and whether or not we are alone in the universe, we have within ourselves the ability to go beyond the petty differences that cloud our lives and, maybe, find a path toward a future where each one of us is at peace.