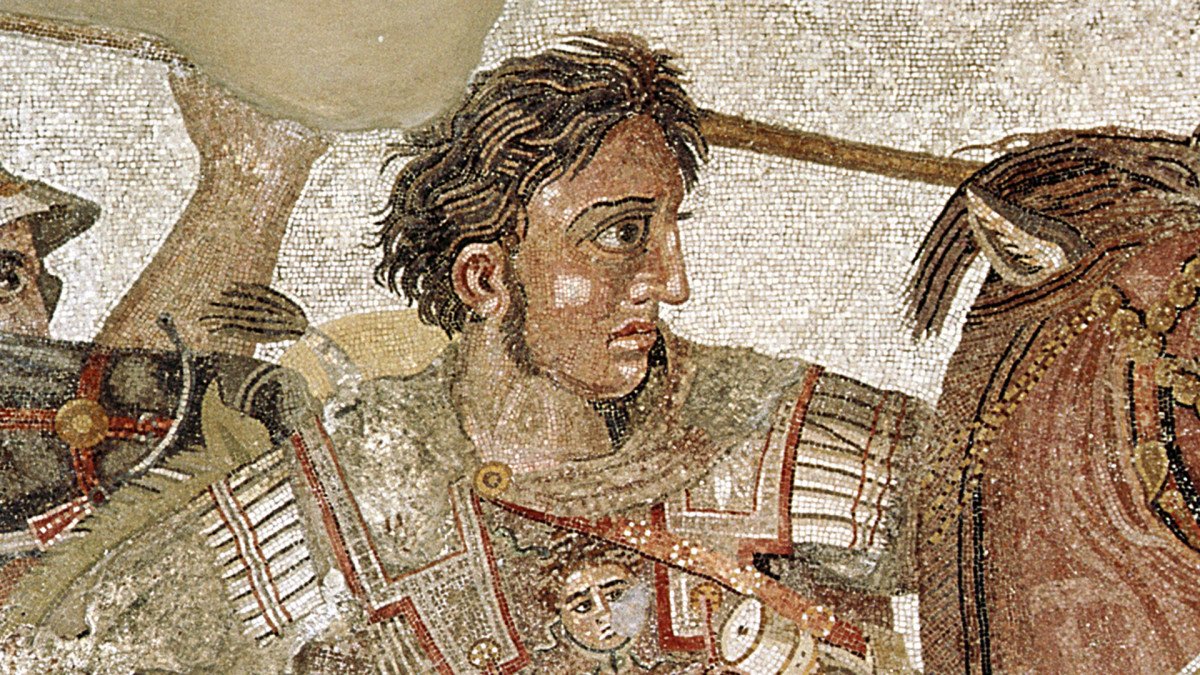

Alexander the Great | The Conqueror of the World

“I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep lead by a lion.”

- Alexander the Great

He looked out across the field and then back at his formations. The wind was coming in from the west, throwing dust clouds up into the air on his left side. The brown of the dust blended with the armor of the enemy for a moment, blurring them into a single mass that blanketed the horizon.

The sun was high. He felt its warmth mingle with the sweat falling down his neck and vanishing beneath his armor. He turned to his right, seeing his phalanxes in tight formation. A flag was raised. He motioned to the man behind him, who raised another, in turn. And his army moved forward, starting with the phalanx on his right flank.

He turned to confirm the calvary on his left were holding their position and was satisfied to see that they were. The other army advanced on his left. He looked at his enemies’ centerline, made some mental calculations, and steadied himself.

The moment brought a memory of watching the molding of armor when he was a boy. During his education, he was made to watch the metal mold under the pressure of the maker’s will. Violence would bend the metal and countless strikes, one after the other, would force the metal to give way.

He looked at his phalanxes. They had met the enemy on his right and left. The left was reeling back and he ordered a small formation to reinforce them.

He raised his sword to signal his cavalry and charged straight into the center of the opposing line.

Early Life

Alexander the Great was born in 356 B.C. to King Phillip II and Queen Olympias of Macedonia. As prince of Macedonia, he was afforded the finest education and was taught by the philosopher Aristotle who encouraged him to pursue literature, the sciences, and medicine. Even at an early age, Alexander showed glimpses of what he would become through his boldness and drive. One such example was when he was 13, he tamed his favorite horse, Bucephalus, who until that point, no man could control. He would go on to apply this boldness in everything he did, which sometimes caused him challenges both in the pursuit of the throne and in holding together the empire he was to forge.

Throughout his entire early life, King Phillip II was bringing all of Greece under his banner. Through force, bribes, and open war, Macedonian rule was being thrust onto all greeks. Through innovative battle tactics, improved supply chain processes, and sheer will, Phillip moved to consolidate all of Greece and change it from a mass of waring city-states into a unified nation dedicated to a single purpose, the conquest of Persia. These aggressive actions first involved a young Alexander who at the age of 16, was left in charge of Macedonia while his father continued another campaign. During this time a Thracian tribe revolted and Alexander acted quickly to put down the insurrection, driving them from their own territory. When his father returned, he was dispatched to extinguish additional revolts until Phillip joined him in the campaign, and together, they subjugated the remaining city-states, forming the Hellenic Alliance and declaring hostile intentions against the Persian Empire.

Once the Alliance was formed, Philip returned to his palace in Pella and fell in love with the niece of one of his Generals, Attalus. This threatened the ascension of Alexander, who because of his mother was only half-Macedonian. This concern was literally spoken aloud by Attalus during the wedding banquet when in a drunken stupor, he prayed aloud that the marriage between his daughter and Phillip would yield a legitimate Macedonian heir. Alexander responded to this by throwing his cup at the man and yelling, “What then am I? A bastard?”

In the wake of the dispute, Alexander and his mother fled until an agreement was mediated between him and his father. It became apparent that Phillip had no intention of handing the throne over to anyone but Alexander, and as a result, made peace.

One year later, Phillip was assassinated by the captain of his personal guard, and Alexander was crowned King of Macedonia. After learning more details about his father’s death, Alexander believed that the Persians had helped orchestrate the assassination and swore revenge on Darrius and all of Persia. Once, King, he had several political opponents executed. He continued this purge until all power had been consolidated to his throne and turned attention to the conquest of Persia.

Moving East

Even as Alexander reviewed his father’s plans for the Persian conquest, more problems arose for him at home. Several city-states began to rebel against Macedonia as a result of Phillips's assassination. Even as Alexander was planning to cross into Asia, news reached him of uprising along his northern borders. He marched against armies in Thrace and Illyria before turning south again to put down revolts in Thebes and Athens. Athens and other city-states decided to back down at the approach of Alexander’s armies, but – as discussed in our podcast about Epaminondas – Thebes resisted. As a result, Alexander raised the city to the ground, killing every living thing and dividing the territories between other Boeotian regions.

After the destruction of Thebes and the slaying of all its inhabitants, Greece was temporarily at peace and Alexander once again turned his attention to Persia. He crossed into Asia Minor in 334 BC with over 48,000 soldiers and 6,000 cavalry. Reaching the shore, he threw his spear into the sand saying he accepted the gift of Asia from the gods.

The main force of his army comprised phalanxes, which were made up of battalion blocks that comprised 16 rows of 16 men, for a total of 256 soldiers per unit or block. Each soldier carried a sarissa, an 18-foot pike that gave them a decisive advantage during an attack or defense. In addition to the phalanxes and other soldiers, he had seasoned calvary. Combined, the two groups would be positioned on the battlefield to amplify one another. Called the hammer and anvil strategy, Alexander would use his phalanxes strategically to form a block of blood and chaos in his enemy’s lines while the calvary swung around and crushed the remaining combatants. Both maneuvers would pin the army under the pressure of being assaulted from both sides again and again. He would refine this tactic in every battle throughout his campaign.

Alexander engaged the first Persian army at the Battle of Granicus, where he was almost killed due to be lured into the river by the opposing general. Instead, the Persian line broke in the wake of his army’s onslaught. He marched on, taking over the provincial capital of Sardis and moving along the Ionian coast while expelling the tyrants and installing democracies. He then conducted his first large-scale siege of Caria where the Greek leader fled to his naval fleets in the Mediterranean Sea. Alexander took control of all coastal cities as he marched, some with force and others with fear. After this, his army marched north to the city of Gordium where he solved the Gordian Knot. According to folklore the person who could solve and untie the knot was to be the King of Asia. Alexander learned this prophecy, and after stating it didn’t matter how the knot was undone, simply walked up and hacked it apart with his sword. As he advanced, he conquered. As he conquered, he replenished resources, armor, and men in his army. This onslaught continued until he met Darius the III, ruler of Persia, on the battlefield of Issus in 333 BC.

The Battle of Issus

At Issus, Alexander faced a much larger, and more powerful foe. In total, his forces numbered close to 37,000 while Darius’s army totaled around 60,000. Darius drew his battle lines in a way that would allow his forces to outflank Alexander and began his assault with calvary and mercenary phalanxes who attacked Alexander’s left flank.

At first, the battle was not going well for the Macedonians. The sheer volume of forces overwhelmed the left flank, which was further supported by additional troops. Seeing this, Alexander led a charge into the Persian center, punching a hole straight through their line. The attack was so violent and fast that the surrounding Persian forces began to waver. Alexander wheeled around the Persian positions from the rear and circled back to charge straight at Darius. Seeing his, the Persian Ruler turned and fled in his chariot. Witnessing their leader run away, the Persians lost the will to fight and tried a tactical retreat before descending into a rout. Alexander and his army continued to mow down Persian forces who held their ground and then pursued the routing soldiers until night fell when they found and captured Darius’s wife and children – whom he treated very well – in the nearby encampment.

The result of the Battle of Issus was a decisive victory for the Greeks and began the decline of Persian power. In total, it is estimated that casualties for the Macedonian army were 452 killed versus 20-40,000 Persians. It was the first time in history that a Persian army had been defeated with the King on the field.

Continued Conquest & the fall of Persia

After his victory, he marched south toward Egypt to assault the city of Tyre. Unfortunately, its high walls and his lack of a functional navy required a siege, which turned out to be long and costly. The soldiers of the city were ruthless in their defense, even displaying captured Macedonian corpses on the ramparts as a warning to Alexander. In answer, he utilized the Persian ships that had come under his banner during his conquest, giving him around 80 ships. With his new navy, he blockaded the port of Tyre and then surveyed the high walls for weaknesses. Once found, his armies launched an assault on the walls until sections began to fall. Alexander is said to have participated in the assault himself from atop a siege tower. Once the city fell, he pardoned all who were inside of the temples within the city but slew all other men of fighting age and sold over 30,000 of its citizens into slavery.

After the fall of Tyre, he marched to Egypt where he encountered little resistance due to the news of his victories, being viewed as a liberator. He honored the traditions of the Egyptians and even made sacrifices to his gods in their temples, following the rituals native to the region. For this, he was even more welcomed and pronounced the son of a deity, after which Zeus-Ammon was referred to as his true father. During his time in Egypt, he founded Alexandria which became one of the greatest cities in the world.

After Egypt, he marched toward Babylon but adjusted his route when he learned of Darius amassing another army near the plain of Gaugamela. There they met again in battle on the plain, and once again Darius was defeated and fled the field. This time Alexander and his forces chased Darius and his army over 35 miles. The king escaped and fled with Greek mercenaries into Media.

Alexander marched toward Babylon occupied it. There he rested and formalized his conquest of Persia by ceremoniously burning down the palace of Xerxes, singling that it was almost at an end. He continued to pursue Darius until the former King was murdered by one of his own men. Alexander found his body and had it sent with honors to the royal tombs at Persepolis. With the death of Darius and the land, his Panhellenic war of revenge was finally at an end.

Limits of Mortality

In the early summer of 327 BC and with most of the known world under his control, Alexander marched into the India subcontinent. Much of the territory was unknown to him, so he depended on former Persian officials and maps to gain an understanding of the territory and possible opposition. After crossing the Hindu Kush mountains, he divided his forces, splitting his soldiers from his siege train to cover more ground at a faster rate and obliterating any forces that stood in his way. This came to a head in 326 BC in the Battle of Hydaspes where he masterfully defeated a force much larger than his own and gained a vast region of territory. And still, he marched on.

By this time, his army was exhausted. Though they had gained many treasures and partaken in the spoils of war, they had been marching and fighting non-stop since leaving Macedonia. They had been complaining of missing home, their wives, children, and wanting to settle back down. At first, Alexander pressed them to go on, citing their many victories and their unstoppable advance. It was only when his generals intervened on behalf of the soldiers that he acquiesced and decided to turn back.

On the march back to Macedonia, Alexander checked in on his conquered territories and executed any leader who had either mismanaged his providence or abused the population. He made it to Babylon by 323 BC and in June of that year, fell ill from an unknown ailment. Alexander the Great died at the age of 32, having conquered the entire known world and beyond, covering 3,000+ miles, all in a mere 13 years.

Legacy

Alexander the Great is one of the most fascinating people who ever lived. As a result, countless books, articles, and pieces of art have been written about him or inspired by him. Through his conquests he spread Hellenism beyond the confines of the known world, expanding Greek culture, thought, and practices in a way that fundamentally changed the course of history. In addition, he send vast amounts of treasure back to Macedonia, adopted foreign customs and ceremonies, and replaced tyrannical rulers with provincial democracies.

As said on another podcast, it is important to note that while Alexander is remembered as being great, it is widely accepted that his conquests wouldn’t have been possible without the work of his father. Phillip II forged new supply chains, developed advanced military technologies, and created battlefield tactics that enable him to subjugate all of Greece. Alexander employed all of these in his conquest, but with the added tenacity and will that set him apart.

When a blacksmith uses a hammer and anvil to shape a piece of steel, time and care are required. The care taken with each strike to mold the metal into a form that has purpose must be intentional, thought out, and precise. It cannot be too fast or too violent, lest the steel break, forcing the blacksmith to begin anew. Like a blacksmith uses his hammer and anvil to shape metal into a tool, so Alexander forged a Greek nation into an empire.

The same drive that Alexander used in his conquest is widely considered the reason for the fall of his empire after his death. Instead of a lasting empire, he instead forged conquest. Instead of molding a piece of beauty that would last the generations, he created a tool that he would use to achieve his goals. The forged iron that was Alexander’s empire was too hot and the hammer strikes too violent for it to survive the ages. Regardless of what happened after his death, Alexander’s life, mission, genius, and strategy were unapparelled and responsible for the world we have today.